Easily noticed because of the hardening of the skin, scleroderma is a relatively uncommon autoimmune condition that affects approximately 300,000 people living in the U.S. each year.

The term scleroderma comes from two words: sclero (hardening) and derma (skin), according to the National Scleroderma Foundation. Also known as systemic sclerosis, scleroderma happens when a person’s immune system overproduces collagen. The collagen becomes thicker in and around several organs, including the skin.

Recognizing signs of scleroderma

There is not necessarily a single telltale symptom that points directly to scleroderma. It can be a combination of signs and symptoms, including:

- puffiness or stiffness of the hands

- puffiness or stiffness extending up arms, trunk (chest, upper back, abdomen)

- telangiectasias, or multiple tiny broken blood vessels, on the cheeks, nose, lips, arms, upper chest

For some patients, they may not be able to open their mouth as wide as they used to because the skin has stiffened on the face.

Sometimes scleroderma can be mistaken for other conditions like arthritis or sun damage When a trained dermatology provider begins to look at a patient as a whole, the picture becomes clearer.

“A patient may not realize that their skin is tightening or growing puffy because it is such a gradual thing,” said Dr. Nana Duffy, MD, a board-certified dermatologist with Genesee Valley Dermatology & Laser Centre in Brighton.

Risk factors and diagnosing scleroderma

There are some factors that increase a person’s risk of developing scleroderma, including:

- environmental exposure to silica

- family history

- race (African American, Native American patients face increased risk)

Research suggests a person with a higher number of telangiectasias is more likely to develop a condition called pulmonary artery hypertension later in life.

If a dermatology provider is concerned about the possibility of a patient having scleroderma, they will order bloodwork to help confirm the diagnosis. Based on the results of the bloodwork, the patient may also undergo imaging such as an EKG, EGD, pulmonary function test, and/or chest CT scan to determine if the sclerosis is only showing up with skin or if it might be affecting organs internally.

Once a diagnosis has been made, patients will be referred to a rheumatologist who can help to manage symptoms as needed.

Treatments and resources for scleroderma

While there is no known cure for scleroderma, rheumatologists can prescribe medications that help to suppress the immune system. Since the patient’s immune system is causing an abnormal production of collagen, the collagen formation process is stopped when the immune system is shut down.

“While it is very difficult to reverse the effects of scleroderma, medications like CellCept and rituximab can prevent it from affecting more organs or more areas of skin,” Dr. Duffy said.

The longer a person goes without treating their scleroderma – whether diagnosed or undiagnosed – the more challenges they might face. For example, a patient might gradually lose mobility or function, for everyday tasks like opening a jar or buttoning a shirt.

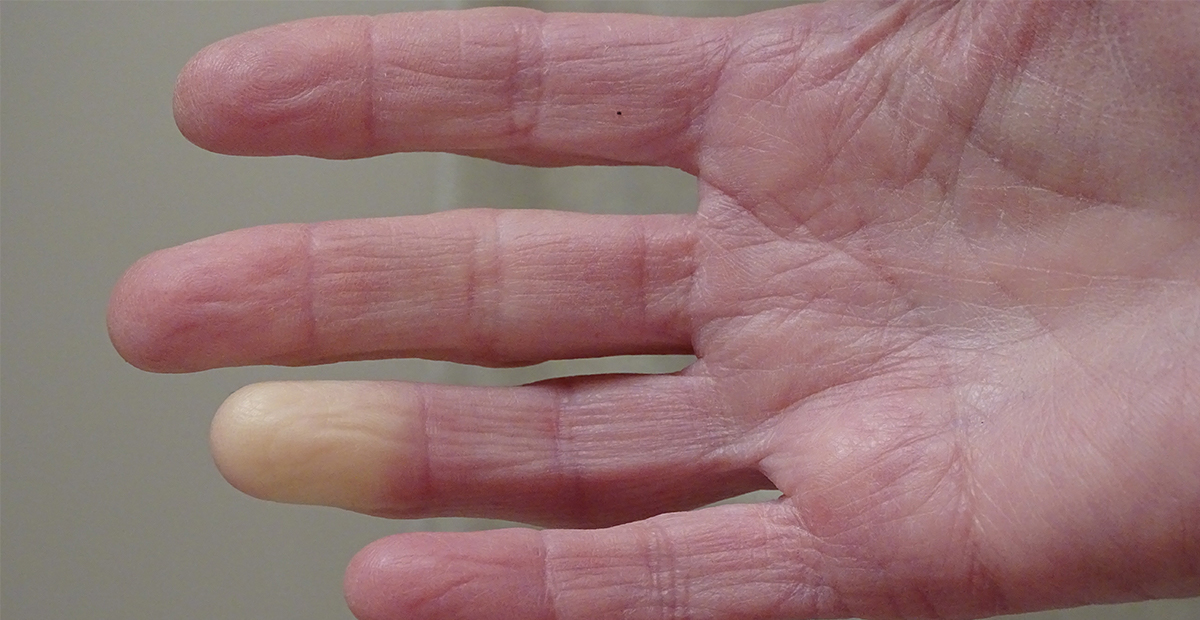

Many patients develop Raynaud’s syndrome, which causes the fingers to change color in response to the cold (i.e., turning purple, blue, or white). Another serious concern arises when scleroderma affects other organs, which is called diffuse cutaneous scleroderma. The further it progresses, the higher the chance it can lead to lung, heart, or kidney damage.

Since scleroderma is a fairly uncommon condition, people who live with it often feel isolated in their experience. The National Scleroderma Foundation: Tri-State Chapter is a non-profit organization with a presence in western New York that helps patients advocate for themselves and connect patients to tell their stories with the disease.